Modernism and the Post War Period

- Nov 25, 2021

- 14 min read

Updated: Dec 1, 2021

can you separate the person from their work? What are the ethical issues of a great architect who has bad politics, racism, etc?

Modernity:

Modernity is the individual experience of intellectual, social and otherwise conscious freedoms. It evolved following a period of drawn out focus on the past and its restrictions. It is the idea that every day is new and ever changing. The current state is different than the past in more than its temporality. Even more so in regard to the future, there is a focus on progress and inherent to that; change. Modernity provokes social and cultural tendencies as well as artistic outbursts in the form of modernism.

Modernization:

The process of general development and “progress”, in the form of; technological, industrial, social, formation of the metropolis, population growths, establishment of bureaucracy, mass communication, emergence of capitalist markets, and democratization. It is sometimes referred to as the most objective aspect of Modernity (perhaps a cause or an effect of Modernity..). It is clear that around the world there was specific and measurable changes in all the aspects above.

Modernism:

Cultural tendencies and artistic movements focused on the future as well as a desire for progress. Made up of theoretical and artistic ideas that promoted the concept of self improvement as the first step toward global human improvement.

Authors in the field of architecture and sociology such as Charles Baudelaire, George Simmel, Marshall Berman and Hilde Heynen have written extensively about the notion of modernity. There seem to have existed two points of view within the arguments of each of these writers; One explaining the need for continued progress and relentless change, the other more casually stating the many intense contradictions and complexities of modernity. Authors immersed in the time between the 1900 and 1980 are hardly expected to understand modernity because they had not seen it through its full cycle. Although contemporary historians today will be more ready to admit the flaws and problems that were inherent to modernism. Contemporary historians also have the power of hindsight and the ability to analyze the modern age in a way no one from within modernity could have truly perceived.

There is intrinsic beauty in styles formed within their own time. During modernity, Charles Baudelaire argues that artistic intent in creation should do so with their own “modern spirit”. Something recreated based off the past lacks this spirit. In addition Baudelaire continues with an explanation of the specific clothing, smiles, and “the look” of a time period. No doubt there are things a la mode within each era or period, Baudelaire simply states that the attempt to discover and pursue the spirit or look of modernism is of highest priority. It is sacrilege to try and imitate old masters in a new setting. The time is gone, forget the past. Each era has its own form of beauty and so, Baudelaire says in the 1840’s, there exists a form of beauty in the current period.

Georg Simmel says, the metropolis holds significant sociological, cultural and mental influence on the individual who inhabits it. There is a specific change that the brain undergoes when becoming engulfed by the metropolis. This change is based on the notion of brain stimulation. The city with its fast pace, quick glances, and perpetual motion is a hotspot for such stimulation. Simmel points out that after a specifically prolonged stimulation of the nervous system, the brain will cease to feel such stimulation and become oblivious to it. The metropolis exposes the individual unending seas of people they will never know. This simple fact makes their own actions and relevance within the general metropolis quite unexceptional. There is a general indifference, when living in a metropolis, toward one’s common man. Simmel even goes as far to say there is an inherent hatred for one another, perhaps drawn from a fear of an unknown. Individuals have learned to be reluctant in trusting any person they confront within the quick and go lifestyle of the metropolis. The modern city reduces men to very primitive instincts, oddly enough; the constant pressure to compete, attain personal comfort, and outdo one another takes their spirit.

Modernism and Modernization are two vastly different concepts. Modernization is rooted in objective understandings and improvements to industry and socioeconomic processes. Modernism is loosely backed by artistic notions and theoretical propositions for the potential answers to the complexities of modern life. Heynen takes a different point of view in respect to Charles Baudelaire and Georg Simmel. Heynen relays the idea that architecture is forced between these two unrelated proponents of Modernity. Architecture, a highly “cultural activity” (related to modernism) is forced to deal with issues of power and money (related to modernization).

He speaks briefly about postmodern architecture and how it is sometimes confused with being “after” what is known as modern. Heynen realizes, with his separation as a historian, that modernism was a very complex thing, far more so than many architects of the time could’ve perceived. There were clearly branches of what is known as modernism that accomplished varying degrees of fame. Although heynen argues that postmodern architecture highlighted the paradoxical complexities of modernism and its key issues.

These “fissures” that exist in modernity and the constant oscillations that riddle modernist ideals are simply a product of the way modernity sought to support itself after its rejection of tradition and the past entirely. There was a form a desensitizing that occurred throughout the modernized world and through the metropolis that few people realized the swift change that had occurred under their noses. After some problems became evident with the Modernist process some chose to salvage Modernism with poetic changes and others, such as Mies Van Der Rohe, embraced it in an unquestioning pursuance of glass, steel and “nothingness”.

Adolf Loos

Adolf Loos seems to be a man of incredible principle despite his vulgarity as a human being. His writings hold a poetic tone to the extent that even some of his most radical ideas can be considered soberly. The fact that he was a pedophile and a racist make his lack of fame in life pretty clear. His ideas only took flight posthumously once they could be separated from the man himself. It seems he is very much in line with some of the thoughts of the high modernist of the 20th century capitalist. However, in the late 19th century up until the first world war, as modernity seems to be taking its first large steps toward a cohesive “style of the epoch”, there are still many people who find solace in the past. Loos speaks to this idea by labeling these people stuck in the past as stragglers. In his most famous piece “Ornament and Crime”, Loos talks about the concept of ornamentation and its ill place in a modern society. Loos makes some interesting points regarding aristocratic society as well as the nature of the craftsman. He speaks to the causal nodes of ornamentation itself; the honour and willingness to make well crafted pieces (clothing, furniture, buildings) and the affluent ruling class that seeks to perpetuate itself through the continuation of ornamentation and subsequently the subjugation of the craftsmen. His distaste with ornamentation is obvious, on the other hand, Loos holds dear the craftsmen and their ability to discover form and style within their own means.

Loos blames the architect for his shady work in uprooting or reforming the very progression of style in the century leading up the the first world war. He believes, that only until “recently” (around 1910), men of trade had begun to find the modern sensibility within their work, something the architect had belittled with his drawings and abstract ideas based on principles well past their prime.

Loos argues that the basis for architecture was one of false ideals. It originated out of the builder and merged with the artist. It is clear that architecture is a creative practice. Perhaps creativity is too much for a profession so ingrained in culture and the daily lives of people. It is possible that on a smaller scale, aesthetic and stylistic choices gain much more importance to the individual. The work of the craftsmen with regard to various common objects such as shoes, belts, purses, streets, tables, chairs, cups, silverware, etc, is far more effective in discovering a true style. This is most true because the architect is too involved with stylistic discovery based on knowledgeable sources from the PAST, while the craftsmen makes discoveries in his own shop with his own hands.

POST-WAR

Post war modernism was largely defined by an anxiety of the rapidly changing social, cultural and political environment of the world. It is difficult to analyze the progression of modernism as a single entity and instead it must be regarded as a pluralistic yet cohesive set of ideals that were pursued at varying intensities. To understand the way that modern architecture changed at the turn of the century, it is necessary to categorize architecture and subsequently the architects of the time into socio-political groups; the Consensuals, the Reformists, and the negative critics. After the devastation of two world wars and an unseemly obsession with mechanization, many were anxious to find a continuity amidst the dynamism that enveloped modern society and technology. It became apparent that modernism must be questioned and as a result there was a crisis in rational thought. In a period of such rapid innovation, it was clear that the idea of change was intrinsic to modernism, however the idea of change was interpreted differently. Some prominent architects believed in the reconceptualization of modernism known as situated modernists, through an increased focus on site, community and the individual experience. Others continued to refine ideas of the machine from earlier in the century.

Architecture before and after the war was heavily influenced by its political environment, and it is clear that modernism had political direction, founded in its social and cultural interests. The rise of capitalism and its subsequent marriage with democracy, through consumerism and mass production enabled facets of modernism to undertake corporate and large scale public needs. The connection that modernism had with the corporate world is most easily identified through the International Style, which invaded nearly all major cities of the world today and is easily construed as true modernism following the world wars. The copy and paste nature of modernism at this point following the war was beginning to lose its authenticity and starting to promote a notion of excess, perpetuated literally by consumerism and the high rises of the international style. The constant oscillation between what is needed and what is wanted seems to define much of the anxiety that existed in architecture following World War 2. The pursuit of mankind to further himself was juxtaposed with the danger that can come with the endless pursuit of innovation and change . Within the political dimension of modernism, there were contradictory influences having to do with the conflict between capitalism and communism. Some architects sought the embrace of democracy and capitalism while others saw this connection as the downfall of modern society as well as a liability to individuality.

At its inception, modernism sought to find a new spirit of the epoch, it embraced new materials and promoted avant-garde design. This spirit, was perhaps change itself. In a world that had seen more innovation in 50 years than it had ever before, the idea of change was quintessential to modernism. As a result many believed that pursuing the glass box, rational thought and functionality purely for the sake of function was not the way forward. The many paradoxes of modernism can be seen through its attempt at utopia in a clearly dystopic world. Some believe that modernists were naive and perhaps ignorant in designing for the common man while in reality losing a sense of place, individuality and comfort. Postwar modernism was a crisis in rationality. The era prior was known as highly functional and rational in thought. These rational ideas saw prominence throughout the wars in their obsession with mechanization. The machine was overtaking what was once quintessentially human (and the machine kills man literally in the second World War).

There was a desire for continuity in rational thought, but a more organic and emotive rationality was to be conceived. Architects such as Le Corbusier, with projects like Ronchamp, sought to revitalize the idea of modernism with more complex forms and an emphasis on a more sculptural architecture. Perhaps at Ronchamps the necessity for “a step back” or an emphasis of new and provocative ideas is what inspired Corbusier to develop his avant-garde design. Despite this, the project can still be interpreted as postmodern. However, postmodernity was not characterized as fully developing until after 1968, once modernism was pronounced “dead”. The dissolving of the Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne seemed to be one of the breaking points in modern architecture. The young architects of the congress, the generation 56’, were in unrest and criticized the old masters of modernism for perpetuating an ideal that seemed disassociated with the needs of the “modern man”. The solution is not found in packing homes together and giving them a small park to stroll in but instead in the animation of the individual in projects such as the Case Study House. Even as some continued to pursue a mechanized and prefabricated architecture the more organic rationality behind these newer projects were the product of an anxiety in the future of modernism; mostly brought about from the many contradictions within modernism.

Ultimately, modernism is pluralistic and at some points highly contradictory. As a result, studying the way it evolves and morphs over time requires a regimented system for categorizing a series of highly complex and intricate works of architecture. Unfortunately it is difficult to organize architectural works due to their multifaceted intent as well as their subjective nature. Regardless, modernism, following the second world war took a turn, that turn was based upon the three dimensions of modernism. The political, social and cultural aspects of modernism became the determinants from which all architects sought to impact and affect change. Whether they perpetuated the machine or sought more site specific structures, the initiative of the modern architect was one of social progress and individual enlightenment. The splintering of modernism after 1959 was necessary and probably predictable because of the magnitude of work produced after the war (one of the reason modernism as a singular movement is so confusing). Despite this, postmodernity, against popular belief, did not begin at the end of modernism, it was slowly exposed through continuous production of work and the the eventual realization of the some of the shortcomings of Modernism.

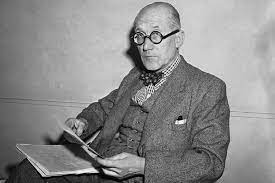

Le Corbusier

Le Corbusier was a man of vast knowledge. His experience in the field of architecture as compared to other major figures during the interwar years, was unparalleled, as were his ideas. He painted every morning and then practiced architecture every afternoon. This routine of raw creativity followed by regimented and measured practice evoked ideas more theoretical than mere design, his ideas on architecture itself were grounded in both art and engineering; pulling from his own daily life. Architecture is always in relationship to man; it is designed based on this relationship and so essential to it that without human scale, architecture would be jarring and misguided. As humanity progressed through the ages, it brought with it a sequence of styles and varying degrees of innovation. Despite this, the magnitude of innovation occurring in the early 1900’s is one unmatched across all ages (As is the current state of progress). Le Corbusier was intent on intertwining man with this infinite change forward through the question of the house. The Machine for Living. In his book, “Vers Une Architecture”, he addresses this question multiple times and ultimately explores the necessity for implementation of industry in the home. He explains the benefits of mass production while also detailing the equally crucial need for art and beauty or as he puts it directly in a note to architects; “Une beauté plus technique. Une esthétique plus près à ses cause véritables”. A more technical beauty is one founded through the pursuit of the aesthetic of the engineer and a newfound precision in measurement and calculation of the artist.

Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris, or as he became known, Le Corbusier, believed that in architecture there is an inherent necessity for measurement and calculation. This idea of something being measured is founded in the very primitive techniques employed by the earliest man. Le Corbusier argues that within the proportion and volume of basic geometric shapes is the very essence of architecture. Man, although perhaps primitive in materials, was never primitive, he always employed basic concepts of architecture. By simply constructing something in the shape of a square or circle, man has already transcended primitivity. It is the act of organizing, measuring and building that create architecture. A man does not believe he is building until his structure begins to organize under an order of measurement and calculation and when he has a feeling of creation! Instead of some random consortium of pillars and tents, man has organized space according to universal orders; universal orders of proportion, scale and mass. Architecture is a “gradation of aims”. It is a series of components organized into a hierarchy that begin to evoke specific connotations and emotions based on this prioritization of these aims.

Le Corbusier believed the essential and specific arrangement of architectural components is what drives the act of creation. Style is the product of good design after years of study and understanding. Le Corbusier makes reference to the Parthenon in large account to promote the elegance in simple yet calculated precision. He notes how the Parthenon with its purest of forms and rhythmic orders of proportion is the most evocative architecture in the way “we are ravished in our minds” and “touch the axis of harmony” (220). This is Architecture; the provocation of feelings and thoughts based on the interplay of mass, surface and light within and between spaces. Style is merely an afterthought. The notion of uncovering the style of the age is a flawed one, Corbusier puts it differently; as discovering, or seeing, the spirit of the epoch. Although he states often that we are unable to see the spirit of the epoch because it is constantly evolving and unfolding around us, it is necessary to understand that style is not created through a set of projects, but instead a plethora of architectural and non-architectural principles (society, economy, technology, industry).

Architecture is often misconstrued as the ornamentation of buildings or as simply art. Ornamentation is not art and architecture is not simply art. Architecture is the harmonious unity between what is perceived and abstract and what is understood and measurable. This idea is one Corbusier reinforces, the engineer and the artist combine to create the architect. The engineer is one who builds with instruments that measure and calculate with precision and skill. The engineer finds an aesthetic in the technical order of things, the mathematical order that drives all of our universe. In a time of ever changing and ever progressing products, lives, industries and people, there is a desire to base all judgements on certainties and on universal orders of understanding nature. (However, Corbusier is not reluctant in criticizing his own peers in saying the architect is lost in this age 1920). The architect on the other hand is lost in academic assumptions and and frilly ornamentation. Even after the war there were still many who doubted the industrial city and the rapid modernization. Even so, one must either adapt, or “go bankrupt” as Le Corbusier puts it, but who continues by saying; the architect is the only profession that does not go bankrupt because it does not require change from decade to decade; it can continue to exist in knowledge founded in the past.

Modernization and the growth of industry has brought about many new building materials and techniques, many of which had not been properly understood in the 1920’s. This was clearly a shame to Corbusier, because he relates the steamship and the airplane to architecture. Both of these, products of industrialization and the first world war, sought to solve a problem and inevitably did, whether it be for killing people from the sky or for ferrying them across an ocean. He believes architects must begin to do the same, however he acknowledges that in order to solve a problem it must be properly stated (and have a plan). This issue that architecture faces is one concerning the house, but the problem of the house had not been properly stated so there was no easy way to address a problem that you do not know how to question. Despite this, Corbusier’s interest in the steamship, airplane and automobile all start to point the way to properly state the question at hand. He begins to slowly unravel the idea that as all things begin to be prefabricated and mass produced, whether it be for transport, for war, or for cooking; why not mass produce the home? The Machine for Living. Le Corbusier doesn’t necessarily jump into exactly how to solve this issue. Of course it takes many years after this manifesto for “Une Esprit Nouveau”, an interest in pure functionalism and representation of harmony in forms and rhythm in plan to be addressed. Le Corbusier is a provocateur, he evokes within himself and others through his writing and his produced work a sense of harmony with the machine. Vers Une Architecture starts to unite a series of very interesting ideas into a question that can begin to be answered. In this book, the aim was to provoke, as Architecture does, and debunk misconceptions of the architect, artist and engineer. This book is ultimately aimed at helping man move forward toward a new style of the age and a more refined daily routine as well as a happier, more integrated man with society and technology.

In hindsight, irrespective of the the pitfalls of the Ville Radieuse and the obvious dilapidation of Villa Savoye, Corbusier's theories and the principles which ruled his bold ideals can be remarked as having serious cultural, performative and social consequences. For example Corbusier would regularly say that all buildings should remain at 18 degree Celsius regardless of their local needs,

"there was no such consensus, and never has been, though later environmentalists' have made equally procrustean propositions such as Le Corbusiers' proposition to maintain a temperature of 18 C in buildings in all parts of the world irrespective of local need or preference." (40 Reyner Banham)

This kind of authoritarian dictation of the needs of people who have no relationship or shared experience to Corbusier or that of his European counterparts is justification in the misguided egotism that Corbusier hoped to impose upon all the uncivilized peoples of the world.

Comments